Introduction

Robots of many types are disrupting the economic and social landscape at unprecedented rates. This disruption is problematic for everyone but is particularly difficult for the Middle and Working Class people whose livelihood is derived from the technologies of the latter half of the Twentieth Century or whose “golden years” are dependent on under- or unfunded pension systems.

The jobs that provide Middle and Working Class livelihoods are disappearing because ever more human beings are losing the competition with ever more sophisticated automated systems. This job loss is already generating discomfort, fear, and anger through much of our population. More importantly, it is already threatening a variety of programs that depend on human employment, the most visible of which is Social Security.

The Social Security Trust Fund surplus is now projected to be depleted in 2037. Unless additional contributions are available, continuing taxes are expected to only pay about 76% of scheduled benefits after the reserves are used up.

Peggy Noonan wrote about her and other people’s confrontation with this new reality as “2016 Moments” in the Wall Street Journal. She reports that each is a “sliver of time in which you fully realize something epochal is happening in politics, that there has never been a presidential year like 2016, … a knowledge that our politics have changed and won’t be going back.”

Noonan sees this in political terms, the nature of discourse, a comparison between men and women of stature and a grubby present. But she comes closest to the crisis when writing of “… my friend John, also had his Moment during the New Hampshire primary. Out door-knocking for Jeb Bush, ‘I was struck as I walked along a neighborhood using the app that described the voters in each house. So many multigenerational families of odd collections of ages in houses with missing roof shingles or shutters askew or paint peeling. Cars needing repair.’

“What was the story inside those houses? Unemployment, he thought, elder care, divorce, custody battles. ‘It was easy to see a collective loss of hope in a once-thriving town.’ He sensed ‘years of neglect and sadness. Something is brewing.'”

That “something” is the visceral human response to the rise of the robots throughout our economic life. Ms. Noonan asserts that “… my country is in trouble …” and she is correct but not for the reason she identifies. Through most of the Industrial Revolution, automation was the source of vastly increased output that could not satisfy pent-up demand. Today, robot production can exceed demand and is laying waste to the fundamental economic and psychic worth of huge and ever increasing portions of humanity.

This evolution to a world economy dominated by robotics is probably unstoppable and may be beneficial but it is also the greatest societal disruption in the history of the world and must be controlled so that it benefits, rather than devastates, humanity.

This effort at control most easily begins with taxation by transferring the tax burden of the replaced human worker to the robotic replacement.

Robots

The coming post-Information Age, the “Automation Age” is credibly on course to replace the last human producing anything with an automated system – a robot – within a period measured in decades rather than centuries. The 21st Century challenges of distributing wealth do not relate to Industrial Age economic concepts such as productive jobs for human beings because employment, jobs as they have been understood for centuries, may no longer exist. Modernity is eliminating jobs through automation (a process that began with the steam loom that led to Ned Ludd‘s fame) and robotics (a whole different level).

The term “robot” has come to mean a variety of things that depend on the topic, the people, and the points to be made. Here, we use the word “robot” to mean any automated system. A robot can be:

- An automated device on a factory floor;

- A piece of software that auto-dials a phone;

- An automatic dishwasher in the home;

- A walking, four legged mechanical pack mule;

- A car that automatically parks, breaks, or even drives long distances; or

- Almost anything that does not require constant attention from a human operator.

Automation Versus Robotics

Automation, in its purest sense, increases a single worker’s productivity. For example, the air-powered nail gun seen on every construction site today does not eliminate the carpenter; it allows the carpenter to drive nails more quickly. This increase in the carpenter’s productivity allows the carpenter’s wages to rise and reduces the consumer’s cost. As long as there is sufficient demand for housing to provide employment to every carpenter who wishes to work, automation is the proverbial win-win-win situation. The employee enjoys high wages, the consumer enjoys low cost, and the government benefits from the taxes collected through full-employment.

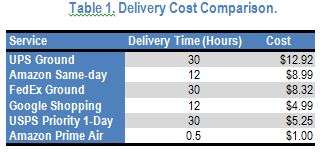

Robots eliminate the need for the worker. For example, a robot or drone that delivers a package from a warehouse to a consumer, as Amazon proposes to do with Prime Air by 2018, eliminates the delivery truck driver’s job entirely while it significantly cuts the delivery time and consumer’s cost as shown in Table 1. While the consumer again benefits from low cost, that benefit is gained from lost jobs and lost taxes. The result is now win-lose-lose.

Robots eliminate the need for the worker. For example, a robot or drone that delivers a package from a warehouse to a consumer, as Amazon proposes to do with Prime Air by 2018, eliminates the delivery truck driver’s job entirely while it significantly cuts the delivery time and consumer’s cost as shown in Table 1. While the consumer again benefits from low cost, that benefit is gained from lost jobs and lost taxes. The result is now win-lose-lose.

Disruption

Economic evolution, Adam Smith’s “Creative Destruction,” proceeds slowly and has historically produced value that is greater than the damage it created. Disruption, whatever the cause, is sudden. While disruption can produce great value, it is also capable of causing great economic dislocations because of the speed with which it occurs.

As robots become more capable, they are creating ever greater disruptions at ever greater speeds throughout the economy.

Disruption in Manufacturing

Manufacturing employment rose from 1945 through 1980 as shown in Figure 1. This was driven, in large part, by its own success and early forms of automation. Automation products for the home (e.g., automatic washers for clothes and dishes, electric vacuum cleaners) gave homemakers more time for outside employment. Added outside employment increased family income. Increased family income led to increased demand for goods and services including larger homes that relied on automation and featured luxuries such as central air conditioning.

Unusual, if not unique, economic and technological conditions enabled never before imagined consumer products. Those new products allowed demand to rise with output and full employment to continue to exist. Automation of the home freed people for employment while automation of the workplace helped keep costs under control. It produced more, rather than fewer, jobs and an increasing standard of living.

The jobs lost to robots are gone forever because demand is not limitless; it can only rise so much for each individual. One person only needs so many pairs of shoes and one household only needs so many television sets. Pent-up demand no longer offsets the effects of automation as it did in Ned Ludd’s day when few people had more clothes than they could wear at one time. Unimagined new products are created only rarely.

Those lost manufacturing jobs were the backbone of the economic explosion from the end of WWII to 1980. They only required moderate skills and reliable attendance to produce very high value and they built much of our economy. Their loss has been devastating to the Middle and Working Class people who depended on them.

Disruption in Transportation

The first round of disruption in the trucking industry came from deregulation in the 1970s and 1980s. Before deregulation, trucking provided excellent incomes to the employer and employee through higher prices to the consumer much like other industries that were both unionized and protected from competition such as auto manufacturers and the airlines.

The deregulation process changed the nature of truckers’ employment from a generally unionized workforce that worked for a limited number of major employers operating in a tightly regulated industry to a generally non-unionized workforce that includes a large number of independent contractors. While over-the-road trucker jobs increased from 510,000 in 1974 to 1.8 million in 2014, the unionized portion of those jobs declined from over 300,000 to less than 100,000 over the same time period.

What happened when those unionized truck driving jobs disappeared? The union-based pension funds that the unionized truckers counted on for their retirement faced declining contributions because of a declining number of employers and a declining number of unionized truckers. Inefficiencies and, in some cases, outright corruption that had been tolerated in the regulated environment became unsupportable.

For example, one of the pension funds involved, the Central States Pension Fund, is paying out $3.46 for every $1 received three decades after deregulation. The importance of this net outflow is exacerbated by the Fund’s structure and stock market losses in the Bear Market of 2008-9 according to the Washington Post. The Plan may have to cut retirement benefits by an average of 22%, and up to a maximum of 70%, for 270,000 retirees.

Central States is the proverbial “tip of the iceberg.” In the longer term, “This is going to be a national crisis for hundreds of thousands, and eventually millions, of retirees and their families,” according to Karen Friedman, executive vice president of the Pension Rights Center.

The price competition allowed by deregulation is also squeezing trucker incomes. Salaries have only risen from $32,500 in 1975 to about $40,000 in 2015 when simply keeping up with inflation would have pushed trucker income to $149,179.11 annually. This is making it difficult to hire over the road truckers with a resulting trucker shortage projected to be in the hundreds of thousands of drivers.

The shortage of workers willing to drive trucks at current pay rates combined with price competition is setting the stage for a second, and potentially more devastating, disruption before that of deregulation is fully resolved: the self-driving truck.

Self-driving trucks are now being tested in the United States and Europe. The first “real world” uses are not far off with systems that reduce driver workload or allow a “platoon” of robotic trucks to follow a single leader that includes a human driver. These are likely to be followed by autonomous systems driving on deserted sections of the Interstate Highway System such as that in South Dakota. Drone aircraft and terrestrial robot vehicles are poised to take over the warehouse to consumer leg of a product’s journey.

As with other robotic systems, the self-driving truck provides advantages to the consumer through lower cost. These include:

- No driver salaries;

- No driver turnover with reduced recruiting and human relations costs;

- 24×7 operation to provide increased vehicle productivity;

- Improved fuel mileage;

- Faster “last mile” delivery; and

- Improved highway safety.

Those consumer benefits come at the expense of millions of human drivers who lose their source of income or see it painfully reduced and the government which loses the taxes, including Social Security taxes, that those workers pay. These losses will also exacerbate the problems faced by union pension plans. Again, it is a win-lose-lose result.

Disruption Beyond Transportation

According to Bloomberg, technology, and especially automation and robotics, is poised to eliminate five million more jobs worldwide by the year 2020. If these were only manufacturing jobs, that is to say if other jobs were immune from robotic takeover, the issue would be simpler but that is not the case. According to cnbcnews, endangered jobs include pharmacists, lawyers and paralegals, drivers (already covered), astronauts, store clerks, soldiers, babysitters, rescuers, and sportswriters and other reporters. McDonald’s is experimenting with kiosks that do the job of counter staff. Robots can now fillet fish with lasers and build houses using three-dimensional (3-D) printing . The list goes on and on.

Shailesh Modi reports from a Singularity University conference that disruptions in medicine (e.g., IBM’s Watson, smartphone apps such as Tricoder X), automobile ownership, insurance, real estate, electrical power, water supplies, manufacturing through 3-D printing, and agriculture are all on the horizon.

The “Retraining” Myth

Retraining has long been the standard approach to helping those who lose their income to economic disruption. The challenge is what these people should be retrained to do, especially as it relates to providing an equivalent income.

According to Business Insider, The 21 best jobs of the future, that is to say the 21 jobs with the fastest growing demand for employees in the foreseeable future will be:

- Registered nurses

- General and operations managers

- Software applications developers

- Computer systems analysts

- Physicians and surgeons, all other

- Accountants and auditors

- Management analysts

- Computer and information systems managers

- First-line supervisors of office and administrative support workers

- Personal financial advisers

- Physical therapists

- Market research analysts and marketing specialists

- Software systems developers

- Medical and health services managers

- Wholesale and manufacturing sales representatives

- Lawyers

- Licensed practical and vocational nurses

- Electricians

- Financial managers

- Nurse practitioners

- Elementary school teachers, except special education

Of these 21 jobs, only three do not require post-high school education; five of them are related to health care; and four are Information Technology based. Few of those most affected by automation – truck drivers, assembly line workers, counter personnel – are likely to possess the intellectual characteristics or educational background needed to be “retrained” for these jobs.

It is also fair to note that some of these 21 jobs are also threatened by automation. Registered nurses and physicians may be supplemented by artificial intelligence systems such as IBM’s Watson and practical nurses may find “last mile” delivery drones to be their direct competitors for some services. Watson is also adept at the legal research now done by paralegals and junior legal staff.

Triage

Twentieth Century thinking provides a limited toolset with which to address the results of the Automation Age’s disruptions on employment:

- Retraining the affected individuals;

- Transfer payments from workers to non-workers; and

- Borrowing to fund shortfalls.

These tools are inadequate to address a future in which the last human worker is replaced by a robot: no jobs to be trained for, no workers to tax, and no tax revenue to pledge as the basis for borrowing. New approaches are needed to address employment, economic, and social disruptions that are real, rapid, and raw. The tools to address these disruptions should:

- Slow the inevitable transition from human to robotic production to a rate that society can keep pace with;

- Replace the taxes lost as jobs transition to robotic “employees” as a first step toward the ultimate need of distributing opulence “ untouched by human hands;” and

- Address socially destructive economic robots, e.g., arbitrage stock trading software.

It is also necessary to develop a roadmap to a future social structure in which human beings can thrive without work as we know it but such an effort is beyond the scope of this White Paper.

Tax Robots

Applying taxation directly to robots may best be addressed in three separate, but not necessarily sequential, phases:

- Apply a tax to each robot or automated system to replace the taxes a worker would have paid as it is deployed;

- Develop a tax structure capable of reasonably addressing prior job losses to robotics; and

- Creating a system of taxation to stem the social damage caused by robots that produce profits for an individual without generating any net economic value.

Tax Robots As They Are Deployed

Impose a tax on each robot that replaces a worker as it is deployed in the field as an effective approach to addressing the first two needs summarized above. This fundamental change in the focus of taxation from the worker to the entity doing the work can slow the transition to the Automation Age and replace lost taxes. It is a viable alternative even if it is radical in its appearance.

It would have five very significant advantages:

- The worker equivalence is fairly easy to measure in many (although admitted in far from all) cases, for example, one truck, one driver;

- The tax burden would reduce, but not eliminate, the economic advantage of replacing a worker and slow, but not stop, the transition to the Automation Age as a result;

- Social Security taxes collected would begin to address the demographic issues in the Social Security funding stream as discussed below;

- Income taxes collected would mitigate the taxes lost to worker unemployment; and

- It would be that challenging first step toward fully addressing a transition into the Automation Age.

Importantly, this taxation does not have to be unitary in nature. For example, the first implementations of self-driving trucks are likely to reduce driver workload rather than replace the driver or function in platoons where the lead truck includes a driver can be construed as increasing the human driver’s productivity and taxed proportionally.

Address Prior Job Loss

Technological advances in production techniques have outpaced demand for years with the greatest changes taking place in parallel with globalization’s acceleration during the last half-century. This level of automation is firmly embedded in the world’s economies and must be addressed as a long- rather than short-term process. It includes a variety of issues including, but not limited to:

- Which existing robots or automated systems should be addressed first? For example, this could be last implemented – first taxed, easiest identified, easiest quantified, or any other reasonable approach.

- How should be “equivalent human job” be established for automated systems that have existed for an extended period of time such as automated bottling machines?

- Which systems should be exempt? For example, a commercial dishwasher might replace a kitchen worker in a restaurant but provide a societal benefit as well through a superior job of producing bacteria-free pots, pans, dishes, and cutlery.

An Integrated Taxation System

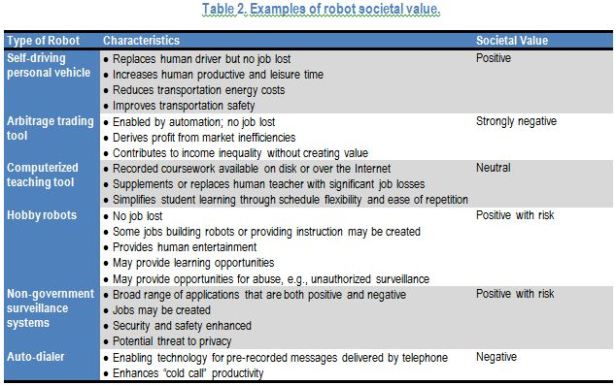

An integrated taxation system of the future is likely to consider the social value produced by the robot. Such valuations are subjective and can be either positive or negative as illustrated by the examples in Table 2, in addition to its impact on employment.

Each robot’s tax burden might be adjusted to include its social value in addition to its human equivalent tax responsibility. This would be a daunting task for a legislature. It will require a formalized method to assess each robot’s impact on employment and assign each robot a societal impact score but more importantly, it will require flexibility to address the unintended consequences that almost surely will be attendant on a radically new approach to taxation.

Robot Taxation And Social Security

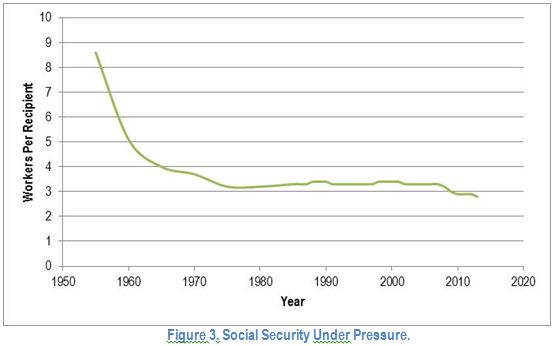

The most important income redistribution program that is under pressure is the Social Security system that relies on current contributions to pay current benefits. The number of workers per recipient has dropped from 159.4:1 in 1940 to 2.9:1 today and is under increasing pressure as shown in Figure 3.

At least three approaches to saving Social Security have been proposed in the United States: raising the retirement age; eliminating the cap on earnings that are subject to Social Security taxes; and increasing Social Security tax rates. Only the first of these addresses the underlying issue of the workers per recipient issue and it does so “at the margins” by slightly reducing the number of recipients and slightly increasing the number of workers. Importantly, it does nothing to address the loss of jobs due to the rapidly increasing number of robotic workers.

Taxing the robots that replace workers addresses the growing demographic problem directly without increasing taxes. Doing so has been suggested in Europe.

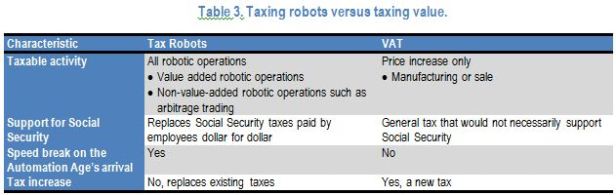

Robot Versus Value Added Taxation

Taxing robotic production is analogous to the European Value Added Tax (VAT) in some ways but it is significantly different in others. It has significant advantages over the VAT as summarized in Table 3.

The Future

Taxing robots is only the first part of addressing societal transition into the Automation Age. Two major challenges remain: finding a way to distribute the opulence that robotic systems produce; and developing a societal model that supports human feelings of self-worth. They are, by far, the greater issue. The storm is brewing but no obvious solution exists.

“The deeper, long-term reasons for today’s rage are not hard to find, although many of us elites have shamefully found ourselves able to ignore them. The jobs available to the working class no longer contain the kind of craftsmanship or satisfaction or meaning that can take the sting out of their low and stagnant wages. The once-familiar avenues for socialization — the church, the union hall, the VFW — have become less vibrant and social isolation more common. Global economic forces have pummeled blue-collar workers more relentlessly than almost any other segment of society, forcing them to compete against hundreds of millions of equally skilled workers throughout the planet. No one asked them in the 1990s if this was the future they wanted. And the impact has been more brutal than many economists predicted. No wonder suicide and mortality rates among the white working poor are spiking dramatically.” – Andrew Sullivan